Suche

Lesesoftware

Specials

Info / Kontakt

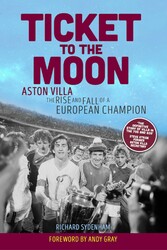

Ticket to the Moon - Aston Villa: The Rise and Fall of a European Champion

von: Richard Sydenham

deCoubertin Books, 2018

ISBN: 9781909245761 , 296 Seiten

Format: ePUB

Kopierschutz: frei

Preis: 5,99 EUR

eBook anfordern

Doug Ellis and His Villa Revolution

‘It was an absolute disgrace what was going on – there was no money anywhere. There was very little to get excited about at Aston Villa other than representing the club and being part of its history.’ – Charlie Aitken

IT WAS JULY 2006 AND DOUG ELLIS WAS A CHAIRMAN ATTEMPTING to deal with a mutiny, two months before he sold Aston Villa for £62.6 million.

Dissatisfied players under the management of David O’Leary took the unusual step of leaking a statement to the media. They complained of a growing culture of frugality that was harming the club’s growth and limiting ambition. They listed cutbacks from significant ones like investment in the team and the scrapping of an £8 million renovation of their training facilities to smaller albeit just as frustrating examples, such as how the club had ceased paying for the team’s masseur, refusing to pay the £300 fee for watering the training pitch and even rejecting an expenses claim for a cup of coffee that the physiotherapist had purchased at an airport café en route to meeting a first-team player. Ellis, known in his early Villa days to tour the ground switching off lights before he left for home, was renowned for his keen eye towards the balance sheet, but these savings were clearly taking austerity to the extreme.

It must be said Ellis’s affection for and attachment to the club could rarely be questioned, irrespective of the thoughts of his detractors. His subsequent sale to American tycoon Randy Lerner would indicate that further investment in the club then would have been foolhardy on his part, even if this cost-cutting logic was seemingly taken too literally. Many fans were grateful for his ability to keep Villa in the black at times when other clubs were facing liquidation through overspending but, equally, fans were frustrated by his overly careful approach to ambition. Fans, staff and the players felt the club should have tried harder to compete with the traditional powerhouses of the domestic game.

So why is this unflattering farewell relevant at the start of this story? Quite simply: irony. It is ironic how journeys start, how they progress along the way and how they end. Ellis’s journey demonstrates the fickleness of football, when his initial positive influence is analysed, devoid of hindsight. However, his desire for control over or at least influence on the player transfers that contributed towards the club’s slide after winning the European Cup scarred his legacy. Ellis was instrumental in dragging the club up from the edge of oblivion in the late 1960s and early 70s, helping to set it on its way to being a European power. Yet, appreciation seemingly eroded over time, as Ellis’s time as either chairman or board member at Aston Villa Football Club would eventually number 36 years, after his first involvement in 1968.

So, what do we know of Herbert Douglas Ellis?

He was born on 3 January 1924, in the village of Hooton, Wirral. He lost his father when he was just three years old, due to pleurisy and pneumonia brought on by gas attacks sustained in the trenches during the First World War. He and his younger sister were then raised by his mother and this tough upbringing instilled in him a will to succeed in life through hard work. Ellis was a keen footballer in his youth but schoolboy trials with Tranmere Rovers were as far as his limited ability would take him – on the pitch. The closest he would ever come in those days to rubbing shoulders with the legends of the game he was so passionate about were occasional impromptu meetings with England great Tom Finney at a bus stop.

This was after Ellis’s work at the travel agency for Frame’s. It says much about the mentality of football stars of that generation that Ellis returned home after work one day to be told by his first wife that Finney – nicknamed ‘The Preston Plumber’ – had been atop their third-floor flat and fixed the leaking roof free of charge, after Ellis had casually spoken of it at the bus stop. His work at the travel agency impressed his boss Wallace Frame enough for him to be sent to Birmingham to manage a fresh enterprise at New Street Station. He arrived in 1948 and the city became his adopted home. Ellis outgrew Frame’s and he started his own operation, identifying the growth areas in the travel industry, exploiting the package holiday boom in the 1950s and 60s. Once settled in England’s second city, he started watching Aston Villa and Birmingham City matches to fuel his appetite for live football. By 1952 he was able to buy season tickets at both clubs, soon becoming a shareholder at Villa. In 1955 he secured shares in Birmingham City also. His association with City jumped to board member status by November 1965 courtesy of his flourishing business reputation locally and the contacts he was making. Curiously, Ellis had first been invited onto the Villa board earlier that year only to be blackballed by other directors who he felt were envious of his wealth and success. Instead, he lent his support to their fierce rivals.

‘You won’t experience any blackballing at this club, Doug,’ director Jack Wiseman told him. ‘We will be happy to have you.’ And his money, more to the point. Ellis would subsequently join Villa. He later considered his three-and-a-half years at Birmingham City an education in how not to run a football club.

‘Ever since I came down from the northwest in 1949, I was an Aston Villa man,’ Ellis insisted. ‘I had two season tickets and would watch Villa one week and Birmingham the next, or whoever was playing at home out of the two. I would work until twenty past one and then leave for the match. Even when I was on the board at Birmingham my thoughts and loyalty were always with Aston Villa. At Birmingham City, there was a general lack of energy, organisation and leadership, which was a reason why I left and also a huge lesson for when I joined the Villa board.’

In 1968, Manchester United, with the much-lauded talents of Bobby Charlton, George Best and Denis Law, became the first English club to win the European Cup, beating Portuguese heavyweights Benfica in the final. It was also the year Villa’s neighbours West Bromwich Albion won the FA Cup through a Jeff Astle goal and finished as the Midlands’ leading club in eighth place of the top tier. Events at Aston Villa at this time were far less auspicious. The team finished sixteenth in the old Second Division in the 1967/68 season, twelve places and fifteen points behind their bitter city rivals Birmingham. The next season followed a similar pattern.

If the team was struggling to be competitive on the pitch, the club was failing on a much greater scale off it. Villa Park was in total disrepair and the board did nothing. The supporters’ ire peaked on 9 November 1968 when they staged a protest against the board at Villa Park and in Birmingham’s city centre after Villa lost 1–0 at home to Preston North End, sending the team crashing to the foot of the table. Just 13,374 attended the match, comparing poorly to the 50,067 that had watched the Birmingham derby a year earlier. The fans had had enough and they railed against chairman Norman Smith, a director since 1939, and the board. The local Sunday Mercury newspaper reported the next day that one thousand supporters had entered the playing area after the game and gestured angrily towards the directors’ box. A police chief superintendent was quoted describing the events as the most violent protest of its type he had witnessed at the ground. The club had reached its nadir, certainly off the pitch.

Businessman Smith was once a local football referee and he cared about Aston Villa. His love for the club during his two years as chairman, though, was more like that of a passive custodian, bereft of any financial powers to make a difference in the improvement of the club on and off the park.

Enter self-made millionaire Ellis and his business associate and London merchant banker Pat Matthews, who would become club president while spearheading Villa’s renaissance by structuring the new board – though he was happy for Ellis to be the new face of Villa on a day-to-day basis.

Villa were desperately in need of a cash injection and new ideas to move forward. Unlike three years earlier, Ellis’s intervention and business acumen were now desired. And the role of Matthews, whose brainchild was a then-unprecedented share issue in the spring of 1969 that raised £205,835, should not be underestimated. That financial influx wiped out the old debt and powered the new Aston Villa towards a healthier future.

‘One of the problems at the Villa in the sixties was the board,’ explained Villa’s legendary left-back Charlie Aitken, who made a club-record 660 appearances from 1959 to 1976. ‘The board didn’t want to spend any money and none of the directors put any money into the club, which wasn’t being run properly. I could see that a mile away. We had a beautiful training ground that they sold to builders for something like £25,000. So we had to go to places like Delta Metals and Fort Dunlop and train at these factory grounds. Doug and Pat Matthews rejuvenated the club when it was on its knees. It was an absolute disgrace what was going on – there was no money anywhere. There was very little to get excited about at Villa other than representing the club and being part of its history.’

Goalscoring winger Harry Burrows further...