Suche

Lesesoftware

Specials

Info / Kontakt

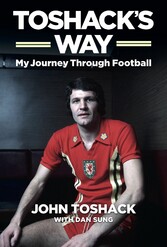

Toshack's Way - My Journey Through Football

von: John Toshack

deCoubertin Books, 2018

ISBN: 9781909245716 , 260 Seiten

Format: ePUB

Kopierschutz: frei

Preis: 5,99 EUR

eBook anfordern

1

Beginnings

RELATONSHIPS SHAPE THE PEOPLE WE BECOME.

My managerial career was shaped by my experiences as a player and the characters that guided me, firstly at Cardiff City and then at Liverpool. Both clubs offered the best education I could have wished for.

My father was a Scotsman, Bill Shankly was a Scotsman, and my Cardiff manager, Jimmy Scoular, was a Scotsman too. They had the same values. They came from villages. They had that same strong, proud, no-nonsense work ethic. There’s certainly something in that Scottish temperament that makes for great managers. Not all Scots are great managers and not all great managers are Scots but, if you look over the years at Shankly, Matt Busby, Jock Stein and Alex Ferguson; you’ve got four there who are right up the top. I’m Welsh all the way but maybe the Scottish influence rubbed off on me.

I’ve worked in a lot of different countries and I’ve been asked whether my sense of adventure stems from my father. It was a big decision for him to choose to leave his family and settle in South Wales, as he did, with little scope for communication with the farm where he grew up back in Dunfermline. Returning to Scotland then felt like a trip to the Arctic.

One trip a year was all he could afford. We used to go up as a family for two weeks every summer: me, my parents and my brother, Colin. We’d rent a Standard Vanguard and take it on a fourteen-hour drive from Cardiff. There were no motorways. We’d leave at four o’clock in the morning, stopping in a layby for a hot meat pie at lunchtime somewhere near Lancaster. Then it would be up over Shap in Cumbria, across the Kincardine Bridge and over the Firth of Forth, before finally arriving at the farm at seven in the evening. There was a real spirit of adventure. Motorways now make the journey a lot easier.

In 1958, when I was nine years old, the Commonwealth Games were being held in Cardiff and the city centre was decked out in ribbons with all the flags of the nations flying on the lampposts. I’d have preferred to stay to watch the sport, but my father’s holiday time was limited so up we went to Scotland where, instead, I played football with my seven older cousins.

At the age of eleven, I was fortunate enough to have witnessed Jock Stein’s first foray into management when he took the job at nearby Dunfermline and my cousin Johnny took me along to watch them play.

My father, George Toshack, was a pilot in the Royal Air Force and based at St Athan in the Vale of Glamorgan when he met my mother, Joan Light, who was a Cardiff girl. They were married in December 1947 and I was born just over a year later in March 1949. I don’t think they’d known each other more than eighteen months and there was never any question of my mother moving to Scotland.

My father was well respected. Before the war, he was a carpenter par excellence. He came to know everybody in the trade in South Wales and Cardiff and everyone knew him. I can see this classic photo of him wearing a tie, his carpenter’s apron and a pencil behind his ear. The people who worked for him spoke so highly of his abilities.

I worked out pretty quickly I would not be a carpenter, having hammered a nail through my own thumb. My father took me back to my mother and told her I was costing him money. He suggested it might be safer for me to do something else. That was that.

We might have had very different professions but the way my father went about his business had a big influence on me. He taught me the importance of discipline in the workplace; a pride in performance. I think this is something that has slowly ebbed away from football and maybe this explains why I’ve fallen out with a few people along the way.

For a young footballer, my father also had what I think is the perfect approach as a parent. You see a lot of parents on the touchline these days shouting away at their kids and giving them a grilling before and after the games on what they need to do and where they’ve gone wrong, but you need to let a good coach do the work. My father knew better than to interfere. He was more likely to be hiding behind a tree to make sure I was focused on my game.

My mother was very proud of me in a more open way than my father. She didn’t mind everybody knowing that she was my mother. She’d always be quick to point out to people what I’d been up to. My dad didn’t like too much fuss. My mother was a wonderful woman, she really was. The most important influence they had on me together was to give me the space to make decisions for myself. I think they were aware of the kind of boy I was and I don’t suppose I was ever going to let anyone decide anything for me. I always had a clear idea of what I wanted but, all the same, they could have got in the way of that and they never did, and that’s easier said than done as a parent.

Decisiveness is an absolutely key attribute of a football manager. When you’re in charge of people, you’ll find you’re faced with decisions virtually every minute of the day. Whether it’s about player selection, buying and selling, working with injuries, organising pre-season friendlies, anything; you need to say yes or no. Perhaps some of those smaller details are taken away from managers in the modern era but, ultimately, the buck still stops with you and you need to have the courage of your own convictions and be able to make up your mind. And, for me, from an early age, I wasn’t frightened to make a decision.

The experience you gain from making your own decisions is something that has gradually been taken away from footballers now, and that’s had a big knock-on effect for those looking to get into management. When I was playing, there were no agents telling you what they thought you should do and taking their 15 per cent. I had just my father, my mother, my brother and myself, and the final decision – and the responsibility – was mine alone.

The change began thirty years ago. Players now are so cosseted there’s a whole part of them that never grows up. I might ask a player what he thinks about the interest we’re getting from another club to buy him and he’ll start telling me what his agent thinks. I’m not interested in what his agent thinks. I want to know what he thinks.

It’s very difficult to see yourself as others see you, but if I had to define myself it’d be as someone who has never been afraid of making a wrong decision or a mistake. I just felt, from an early age, a sense of authority. Life is about making decisions. You can’t say maybe. Maybe is, for me, not a word that tells me anything. If someone answers something I ask with a maybe, I feel like retracting the question.

If I’ve been able to do that, that’s partly because I’d been making up my own mind for a long time. I was captain of the school baseball team, captain of the cricket team and captain of the rugby team too, so I grew up getting used to making decisions.

I played football all the time, whenever I could. I’d even get my mother to make me sandwiches so that I could spend the time I was supposed to be eating lunch at school playing football instead. Eventually, one of the older boys told my sports teacher about me and I was picked for the Under-11 school side at Radnor Road Juniors when I was just eight years old. My sports teacher, the late Roy Sperry, must have had a lot of confidence in me because elevating a kid by a few years to a new level wasn’t normal practice. By then, I already knew that football was what I loved most of all. I played all sports but soccer always had that edge over everything else. If I lost at those other games it didn’t really bother me but when I lost at soccer it hurt.

My parents, though, were insistent that I achieved some kind of academic grounding. I passed my eleven-plus and went to Canton Grammar School, but the problem we had there was that the school didn’t play football. It was rugby only. So on Saturdays, I played rugby for the school in the morning and soccer in the afternoon for Pegasus, the local team in the Cardiff District League; when I dislocated my shoulder playing rugby for the school it meant I missed a trial for the Cardiff Schools’ football side, which put me off rugby a little bit. When the chance came round again, I got my go at the city-wide team and I got in along with a Canton Grammar School pal of mine called Dave Gurney. That made our school think twice about playing soccer and very soon Canton was fielding a team in the grammar school tournament, the Ivor Tuck Cup.

At fifteen, I set a record in the town team and racked up 47 goals in 22 games by the end of my first season. I made it to the Welsh Boys’ side where I scored a hat-trick in my first game, a 3–1 victory against Northern Ireland at Swansea in the Victory Shield.

Suddenly, invitations to trials at Football League clubs began to arrive. A few of the lads in that Welsh Boys’ team with me – Roy Penny, Cyril Davies, the Slee brothers – and I were invited up to Tottenham for a trial in the autumn of 1964 with Bill Nicholson’s Spurs. Spurs had an ex-international called Arthur Willis who had played for Swansea and eventually settled in Wales, and he was always on the lookout for new Welsh talent for the club. Willis had been one of the key players in Tottenham’s push-and-run team that had first won the title in 1951. And, at the time, Tottenham had Terry Medwin, Cliff Jones and Mel Hopkins – all Welsh...